Interesting and helpful information about ways to prevent snake bites as well as straight-forward steps to take in the event of a snake bite.

| On this page: What to do | What not to do | Photos of snakes | Tetanus | Prevention | References |

What to do if bitten by a snake

-

- Call 911 immediately or go directly to the emergency room if there’s even a remote possibility that the snake is poisonous.

Do not wait for symptoms to develop because once the symptoms start, they can progress very rapidly with some venom.(2) - Try to remain calm

Increased physical activity improves the flow of venom into the bloodstream. Keep in mind that even if the snake is venomous, a large number of bites from venomous snakes are “dry” (without venom), and even if the venom did penetrate, the death rate from a venomous snake bite is less than 1% when modern medical resources are used. So don’t panic, just get immediate medical assistance. - Make a mental note of the appearance of the snake

Snake experts recommend not spending time trying to catch the snake to take it to the health care center. First of all, this may delay transportation to professional care, and also, the snake may bite again.- Venomous snakes will leave two distinct puncture wounds, and non venomous snakes may leave marks more like scratches(6). See below for more important features to note.

- Remove any constricting clothing or jewelry on the bitten extremity

Swelling can progress rapidly. - Wash the bite thoroughly with soap and water.(2)

Snake venom contains enzymes that can cause extensive local tissue damage. - Immobilize the bitten area, if practical, and keep it slightly lower than the level of the heart.(2)

- Call 911 immediately or go directly to the emergency room if there’s even a remote possibility that the snake is poisonous.

What not to do if bitten by a snake:

Studies have found that these interventions can cause additional injury as well as delay transportation to professional medical care.(1)

-

Do not apply ice

-

Do not make an incision and suction. A suction device may be placed over the bite to help draw venom out of the wound without making cuts. Suction instruments often are included in commercial snakebite kits. (2)

-

Do not apply a tight tourniquet. However, if a victim is unable to reach medical care within 30 minutes, a bandage, wrapped two to four inches above the bite, may help slow venom. CAUTION! The bandage should not cut off blood flow from a vein or artery. A good rule of thumb is to make the band loose enough that a finger can slip under it. (2)

-

Do not eat, drink, or take any medication (1)

-

Do not use electrical shock. There are absolutely no benefits to the recent theory that electrical shock (from stun guns or spark plugs) will help in the treatment of venomous bites. Laboratory tests have shown only deleterious results.

Two families of venomous snakes are native to the United States:

Pit vipers and coral snakes The vast majority of the venomous snakes in the U.S. are pit vipers, which include rattlesnakes, copperheads and cottonmouths (water moccasins). The other family of domestic poisonous snakes includes two species of coral snakes found chiefly in the Southern states. Coral Snakes are rare but they possess venom more toxic than that of any other North American snake.

Pit vipers get their common name from a small “pit” between the eye and nostril that detects heat and allows the snake to sense prey at night. These snakes deliver venom through two fangs that the snake can retract at rest, but which spring into biting position rapidly. The amount of venom actually delivered by a pit viper bite varies. According to physicians who treat snake bite victims, some 20 to 30 percent of patients who have been bitten by a snake, who actually have fang marks, have not received any venom at all. Coral snakes have small mouths and short teeth, which give them a less efficient venom delivery than pit vipers. People bitten by coral snakes lack the characteristic fang marks of pit vipers, sometimes making the bite hard to detect.

Though coral snakebites are rare in the United States–only about 25 a year –the snake’s neurotoxic venom can be dangerous. The bites of both pit vipers and coral snakes can be effectively treated with antivenin. But other factors, such as time elapsed since being bitten and care taken before arriving at the hospital, also are critical.(7)

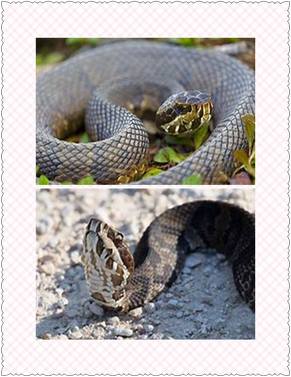

Rattle Snakes: The defining features: Rattle, Triagular head, and Hinged fangs

From the CDC: “This is a “dusky pygmy” rattlesnake, Sistrurus miliaris barbouri, the southern counterpart of the “Carolina pygmy” rattler. It ranges from southern South Carolina, westward across southern Alabama and Mississippi, and south throughout the state of Florida (Connant, 1975). Superficially resembling the Carolina subspecies, it often has a dusted appearance due to the diffuse black mottling in the ground color.

From the CDC: “This is a “dusky pygmy” rattlesnake, Sistrurus miliaris barbouri, the southern counterpart of the “Carolina pygmy” rattler. It ranges from southern South Carolina, westward across southern Alabama and Mississippi, and south throughout the state of Florida (Connant, 1975). Superficially resembling the Carolina subspecies, it often has a dusted appearance due to the diffuse black mottling in the ground color.

Throughout its range, the dusky pygmy rattlesnake inhabits the pine flatwoods, moist prairies and virtually any type of other habitats that offer sufficient cover and are in close proximity to wetlands (Tennant, 1998). Dense populations of this little rattlesnake can be found in many areas of Florida, especially in the moist prairies around the everglades (Tennant, 1998). Dusky pygmy rattlesnakes are one of the species that will readily invade towns and buildings with hurricanes and/or floods, making it an important snake to recognize by first-responders.As their name suggests, the pygmy rattlesnakes are small rattlesnake species that are light gray to brown to red snakes that display a prominent series of round to ovoid black middorsal blotches flanked by one to two rows of spots on each side of the body. A longitudinally-oriented, rust colored middorsal stripe is often present on the anterior half of the body, but may be lacking in some individuals, or obscured by blending with the ground color in reddish colored individuals (Connant 1975). The rattle in this species is tiny and inconspicuous and is capable of producing a buzzing sound that is at best, audible from only a few feet away (Connant, 1975).”

Photo and text courtesy of the Center for Disease Control (CDC)/ Edward J. Wozniak D.V.M., Ph.D.

Water moccasins are indigenous to the hurricane-prone areas in the Eastern U.S.

From the CDC: “This 2005 photograph depicted an “Florida cottonmouth” snake, Agkistrodon p. conanti. When one thinks about snakes indigenous to the hurricane prone areas in the eastern United States, the cottonmouth or water moccasin is probably the first species to come to mind. The cottonmouth is a large dark heavy-bodied snake that ranges throughout a large portion the southeastern United States. Cottonmouths are the largest snakes in the New World Agkistrodon species complex and are the only members of the group that are semiaquatic. Three distinct subspecies are currently recognized; the “eastern”, “Florida”, and “western” cottonmouths. The Florida cottonmouth ranges from the southeastern extreme of South Carolina through coastal and southern Georgia, south throughout the state of Florida and west along the Gulf Coast to the eastern face of Mobile Bay in Alabama.”

From the CDC: “This 2005 photograph depicted an “Florida cottonmouth” snake, Agkistrodon p. conanti. When one thinks about snakes indigenous to the hurricane prone areas in the eastern United States, the cottonmouth or water moccasin is probably the first species to come to mind. The cottonmouth is a large dark heavy-bodied snake that ranges throughout a large portion the southeastern United States. Cottonmouths are the largest snakes in the New World Agkistrodon species complex and are the only members of the group that are semiaquatic. Three distinct subspecies are currently recognized; the “eastern”, “Florida”, and “western” cottonmouths. The Florida cottonmouth ranges from the southeastern extreme of South Carolina through coastal and southern Georgia, south throughout the state of Florida and west along the Gulf Coast to the eastern face of Mobile Bay in Alabama.”

“As the southernmost subspecie of cottonmouths, A. piscivorus conanti ranges from the southeastern extreme of South Carolina through coastal and southern Georgia, south throughout the state of Florida and west along the Gulf Coast to the eastern face of Mobile Bay in Alabama. It’s the largest member of the A. piscivorus complex. Its head is conspicuously marked with distinctive vertical stripes on the rostrum and mental regions creating a “handle bar mustache-like” marking on the rostrum when viewed from the front, an effect that is nicely visible in the specimen pictured here. The head also bears a prominent pair of bilateral dark cheek stripes that are markedly bordered by light areas above and below; a pattern that can be so striking, untrained people accustomed to seeing the less colorful “western” specie, sometimes have trouble identifying the Florida subspecie as a cottonmouth.” Photo and Text courtesy of the CDC/ Edward J. Wozniak D.V.M.

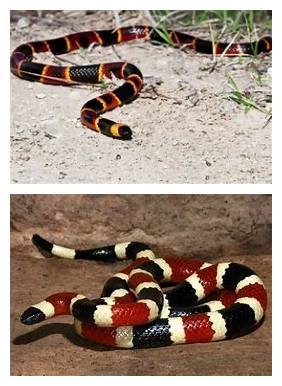

Coral Snakes are rare but they possess venom more toxic than that of any other North American snake

Coral snakes have the characteristic pattern of wide red and black rings separated by thinner yellow rings, and can be readily distinguished from the harmless impostors king, milk and scarlet snakes by the mnemonic “red on yellow kill a fellow”. This potential for confusion, however, underscores the importance of seeking care for any snakebite (unless positive identification of a nonpoisonous snake can be made). It should also be noted that this color rule does not apply to many of the medically important species from Mexico, Central and South America. To be safe, avoid them all.

From the CDC: “In contrast to the pit vipers, the fangs of the coral snakes are short hollow structures and pose little risk to individuals wearing appropriate clothing and footwear. Most human envenomations occur on the hands after a coral snake was erroneously identified as a harmless king snake, and intentionally handled (Kitchens 1987).

From the CDC: “In contrast to the pit vipers, the fangs of the coral snakes are short hollow structures and pose little risk to individuals wearing appropriate clothing and footwear. Most human envenomations occur on the hands after a coral snake was erroneously identified as a harmless king snake, and intentionally handled (Kitchens 1987).

Coral snakes inhabit the hurricane-prone regions of the U.S. which is of importance to those living in these regions, and first-responders offering aid to those affected by such a disaster. (Campbell and Lamar 2004).” Photo and text courtesy of the CDC/Edward J. Wozniak D.V.M.

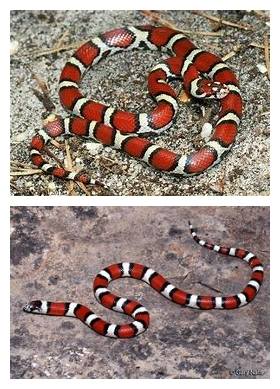

Nonvenomous milk snake:

Yellow is not touching red in this snake.

Yellow is not touching red in this snake.

From the CDC: “This was a 2005 photograph taken of a harmless “milk” snake, which is very similar in coloration to the more deadly coral snake. The similarity in coloration to the coral snake, and the fact that the habitats of these snakes includes hurricane-prone regions of the United States, makes the ability to accurately distinguish these two reptiles from one another extremely important for those living in, or first-responders to these areas after a weather-related disaster. Both the milk snake and coral snake have the characteristic pattern of wide red and black rings that are separated by thinner yellow rings, and can therefore, be readily distinguished from the similarly-colored harmless king, milk and scarlet snakes by the infamous rhyme, “red on yellow kill a fellow”. It should be noted however, that this color rule does not apply to many of the medically important species from Mexico, Central and South America.” Text and photo courtesy of the CDC/Edward J. Wozniak D.V.M.

Tetanus Prophylaxis

Tetanus (Td) injection should be given within 24 hrs. of the bite if you have not had a tetanus immunization in the last 5 years

Ways to avoid snake bites

- Leave snakes alone. Many people are bitten because they try to kill a snake or get a closer look at it.(2)

- Stay out of tall grass unless you wear thick leather boots, and remain on hiking paths as much as possible. Snake bites, such as those inflicted when snakes are accidentally stepped on are nearly impossible to prevent.

- Wear boots and long pants when walking outdoors at night in areas possibly inhabited by venomous snakes.(7) Snakes tend to be active at night and in warm weather.

- Keep hands and feet out of areas you can’t see.

- Look before you reach under rocks or a log. Don’t pick up rocks or firewood. Be cautious and alert when climbing rocks.

- If you encounter a snake when hiking or picnicking, just walk around the snake, giving it a little berth–six feet is plenty. Snakes can only strike within two-thirds the length of their body, so a 3-foot snake could reach up to 2 feet away.(6)

References

- Snake Bites from Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center

- Treating and preventing venomous bites from the US Food and Drug Administration

- Animal Bites from the Mayo Clinic

- Animal Bites from Merck Source

- Snake Bites from emedicine.com

- Ben West, assistant wildlife professor at MSU

- Animal Associated Hazards from the CDC

- Treating and Preventing Venomous Snake Bites from the FDA